The True Story of Two Women from California Who Are Solving All the Mysteries.

By James Renner

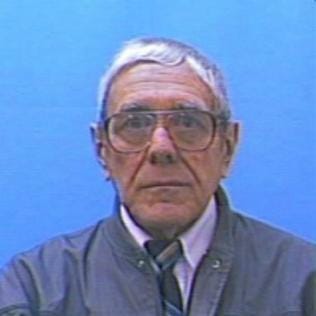

Case Study: Joseph Newton Chandler

They called the dead man Joseph Newton Chandler but that wasn’t his name. He lived alone in an efficiency in a nondescript apartment complex in Eastlake, Ohio, a workaday suburb of Cleveland. He rarely ventured far from home and the closest thing he had to a friend was a former coworker at a chemical factory he once listed as an emergency contact on his employment forms.

One day in July, 2002, Chandler purchased a handgun — a .38 caliber Charter Arms revolver. The old man returned home. He locked his door and windows, turned off the AC. Then he stepped into to his bathroom, faced the mirror, and put the barrel of the gun in his mouth. The last thing to enter his mind, other than that bullet, may have been the dark secret he was leaving behind.

By the time anyone noticed he was missing, Chandler’s body had decomposed in the summer heat and maggots had got at it. It was impossible to lift fingerprints. Police reviewed the paperwork this dead man had provided to the rental office, searching for next of kin. He’d listed a sister, Mary Wilson, who lived at 1823 Center Street, in Columbus. But the address led to an empty lot. It was important they find some relative — he’d left $82,000 in the bank.

The court appointed his coworker as the executor of his estate and enlisted a private investigator — Mike Lewis — to track down Chandler’s family. Lewis used Chandler’s birth certificate to identify his parents and then cross-checked birth records in Buffalo, where Chandler was born, and in that way located a sister. She was rather surprised to hear the news because her brother, Joseph Newton Chandler, had died in a tragic car accident at age eight along with their parents, four days before Christmas, in 1945. The dead guy in Eastlake was not the real Joseph Newton Chandler.

Whoever he was, he’d carefully assumed the dead boy’s identity over several years — first, by obtaining a copy of Chandler’s birth certificate in Buffalo and then by using that document to get a social security number in Rapid City, in 1978, before moving to Ohio. He got a job as a draftsman for the Lubrizol chemical company and earned a reputation there as a quiet eccentric — he liked to listen to the sound of static while he worked.

The Eastlake police ran down every lead they had but the case went cold. U.S. Marshal Pete Elliott heard about the mystery in 2014 while looking for some men who had escaped Alcatraz. Perhaps Chandler was actually one of these fugitives, he thought. Certainly, the man was running from something — why else would he take his true name to the grave? Why would he look at himself while he ate a bullet? To a trained investigator, that suggested guilt and shame.

Elliott located hospital records for the old man. One detailed a trip to the E.R. in 1989, when the man had been treated for lacerations on his penis which he claimed were caused by having sex with a vacuum cleaner. Not long before he committed suicide, the erstwhile Joseph Newton Chandler was diagnosed with cancer and the hospital collected a tissue sample. They still had it. Elliott sent it to the lab. Unfortunately, the DNA was too degraded to be of much use to law enforcement. It seemed like the old man’s true identity would never be found.

Then, on June 21, 2018, Pete Elliott called a press conference in the jury assembly room at the United States Court House in Cleveland.

In the news footage, there’s an amused smile on Pete Elliott’s lips as he steps to the podium to address reporters. He has a whopper of a story for them — the true identity of the man known as Joseph Newton Chandler has been discovered. But not by any cop.

“Now it is my honor to introduce the ladies from California,” he says. “Dr. Colleen Fitzpatrick and Dr. Margaret Press not only put us in the ballpark with Joseph Newton Chandler, they told us the exact seat he was sitting in and then told us who paid for the ticket and the person who paid for that ticket was Mr. Robert Nichols. It’s my honor to introduce the two doctors.”

Elliott steps away and Dr. Colleen Fitzpatrick comes forward. She can hardly be seen behind the podium. “I want to thank the Marshals for trusting us to work on this case,” she says, her face all smile, her glasses perched on top her short, wavy hair. She doesn’t open with an anecdote or charming story. Colleen dives head-long into a partical explanation of Y-chromosomes and proprietary software used to make sense of all of it and much of this was left out of subsequent newspaper articles but one thing was clear — Colleen and her partner had come up with a new way to catch bad guys.

Case Study: Colleen Fitzpatrick

Colleen Fitzpatrick has a vest with forty-two pockets and before she explains how she changed forensic science forever, she wants to explain what each pocket is used for. We’re at her favorite Persian restaurant — Darya, in Costa Mesa. She’s just come off a plane from Cleveland a day after Elliott’s press conference, and the vest made traveling easier.

“It’s a SCOTTeVEST,” she says in rapid-fire, staccato sentences. “It was on Shark Tank, the TV show? It will change your life. Look, you can fit an iPad in this pocket and here’s a pocket you can store your credit cards because it blocks RFID signals so nobody can scan for your information, people do that now, and this pocket is for your glasses and here, the piece de resistance…” She opens a pocket to reveal a card-sized piece of cloth with diagrams sketched on it. It takes me a second. “It’s a map to all your pockets so you can know where everything goes and where everything is.” Before the meal arrives she has sold me on the SCOTTeVEST.

Colleen grew up in Lakeview, that upper-middle class section of New Orleans that drowned in Katrina. She was the oldest of four and her memories of the Big Easy from the 50s and 60s conjures a world that doesn’t exist anymore. A safe, cozy place in a time before Mardi Gras became a bacchanal. Her family had the only pool in the neighborhood and her mother let the Red Cross train kids to swim there. Her father sold silk flowers, wholesale and retail, in a large shop and designed and hung Christmas decorations for businesses in the winter.

From an early age, Colleen exhibited savant-like behavior. She was proficient in French by the time she was four. She skipped eighth grade. And she was always working on some fantastical project.

“Colleen would hold little fairs at our house,” recalls her sister, Bebe. “Like county fairs, you know? With booths and games for kids. One year, she made a spook-house in the garage. You sat in a wagon and she pulled you through.”

The entire family enjoyed thought-provoking games. There were long matches of Clue with the extended family and her grandmother was the reigning champion for many years. Her father taught them to play hearts.

The Fitzpatrick kids liked to collect Mardi Gras beads in the French Quarter and along Bourbon Street and it was always a challenge to see who could procure the most without being indecent. One year Colleen returned with great piles of beads.

“She came up with such a great idea,” says Bebe. “She made this giant clown face, with a big open mouth for a target. She stood on the sidewalk and as the parade came by, she challenged everyone to throw their beads in its mouth.”

Though nobody gave a name to it, it was clear Colleen was different. She thought differently, saw the world differently. She assessed the world in a series of win/loss challenges, looking for any advantage.

“Have you ever seen The Big Bang theory?” says her brother, Tim. “I tell her she’s our Sheldon.”

“People expected her to do something fabulous when she left,” says Bebe.

When it came time for college, though, funds were tight. Much of her father’s income was going to care for her dying grandmother. Colleen had her mind set on the physics program at Rice University but she knew she’d probably end up at Loyola. As the enrollment deadline approached, Colleen focused on her science fair project — she was conducting experiments with a Benham disk. An illusion first discovered by an English toymaker, a Benham disk is a circle with a specific black-and-white pattern of curved lines that, when spun, appears to create bands of color. Different people see different colors and to this day nobody really understands how it works. Young Colleen set out to discover what was going on. She ran a number of tests and constructed variations of the Benham disk to see if it had any impact on the colors produced.

The day her enrollment paperwork for Loyola was due, a telegram arrived at the Colleen’s house. Her science fair project was one of ten in the country selected for an award by Tomorrow’s Scientists and Engineers, a program sponsored by Humble Oil. The prize was $6,000 toward the college of her choice.

“My life is a series of events like this,” says Colleen. “I’m a scientist but science can’t describe everything. We cannot describe ourselves scientifically. How do I describe why we are here? I believe in intuition, in being directed down a certain path because of events like this. Is there a master puppeteer directing our path through life? Or do we engineer it all ourselves? I don’t know.”

In college Colleen studied physics at Rice and earned her PhD from Duke University. Along the way, she became fascinated with an illusion of a different sort — holograms. She taught herself holography, the method of creating a three-dimension image on a two-dimension surface of glass. It was art, it was science. And it required great patience and focus, the glass had to remain completely still during the process. If it wavered even a billionth of a meter the image would not develop. She built a holography lab in her garage and it took her five years to get it right.

Colleen lectured at Sam Houston State University for a couple years but found she didn’t care for teaching. She left for a job with Rockwell International, a defense contractor out of Seal Beach. There, Colleen worked on the laser radar system used in Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars initiative. Later, at Spectron Laser Systems, she was the principle investigator on the LITE Laser for the space shuttle, an experiment that used lasers to identify chemicals and pollution in the atmosphere. In 1989, she founded her own company, Rice Systems, Inc. She continued her work on the use of lasers for high-resolution measurements and bid on contacts with NASA, the National Science Foundation, and DARPA. She was working on the next spacecraft to Jupiter when funding was redirected to a return voyage to the Moon by the Bush administration, in 2005. As a kind of release, Colleen then began writing a book about her other passion — genealogy. Colleen knew there was a way to apply science to genealogy in a way that had not really been done before. Hers was the very first book on the subject, according to Forensic Magazine.

Part of genealogy involves the examination of old photographs in order to identify subjects and time periods. At the time, most investigators were focused on the details of the clothing worn by the subjects in the pictures, trying to identify the manufacturer and time period a blouse or pair of pants was produced. But that method was very imprecise — people could keep the same pair of pants for years. So instead, Colleen studied the thickness of the cardboard the photographs were printed on. She researched the history of cardboard and learned how the thickness increased over time. She also researched the aspect ratios of the photos, which reveals the size of the negatives the photographer used, which in turn identifies the particular brand of camera that took the photo. She built a website — ForensicGenealogy.info — and blogged about her findings.

In 2006, Colleen was contracted by Hebron Investments, an international business that located people whose homes had fallen into escrow due to unpaid taxes in various parts of the world. She worked seventy-five cases, locating people in thirty countries, sometimes using Google translate to communicate. She found them all but two.

After that, Colleen spent some years identifying holocaust survivors who had been taken from their families during the war. She helped expose fraudulent authors who claimed to be survivors of the Holocaust. And she got really good at identifying people using archival records and DNA. The techniques she was using to find these people would soon be used to locate a serial killer.

Case Study: The Canal Murders

On the morning of November 9, 1992, a young woman’s nude, headless body was discovered near a bike path along the Arizona Canal in Phoenix. Police were quick to connect this body to the report of a missing woman that had come in the night before — twenty-two-year-old Angela Brosso had gone for a bike ride along the canal path and never returned home. It was Angela’s birthday. Her bike was never located. Her head was found eleven days later in a canal grate.

Ten months later, seventeen-year-old Melanie Bernas went for a bike ride along the Arizona Canal and never returned. Her body was found in the water the day after she disappeared. She’d been stabbed to death. Her bike was also gone. A serial killer had come to Phoenix.

And for twenty-two years, the man remained unidentified.

In 2014, the 25th International Symposium on Human Identification was held at the Biltmore in downtown Phoenix and several local detectives attended the event to learn about new techniques that could be used in forensic identification. Colleen Fitzpatrick was there, speaking about her attempts to identify the extended family of Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

Colleen offered to meet with the police to explain a new way they might use DNA to find Angela and Melanie’s killer. An officer picked her up and brought her to station. If there was any chance this woman had a new trick up her sleeve, the detectives were interested.

“These murders brought the city to its knees,” says Detective Dominic Roestenberg. “We hadn’t seen anything that violent. By the time we heard about Colleen, we had exhausted all investigative leads. And what she did… it was miraculous.”

What Colleen did was find a needle in a factory of haystacks. The state lab had tested the suspect’s DNA and isolated his Y-DNA profile. Y-DNA is very important to genealogists. Every person has 23 pairs of chromosomes, a mix of genetic information from their mother and father. The 23rd pair, however, is either two X-shaped chromosomes for a girl or an X and a Y-shaped chromosome for a boy. The Y-shaped chromosome is passed from father to son — like a surname. If a person’s Y-DNA profile can be sequenced and compared to other profiles in a large enough database, it’s possible to figure out what that person’s last name likely is.

There are a number of websites with large, public databases of Y-DNA profiles, which are used by genealogists to trace lineage, huge websites like YSearch.org, but also smaller, individual sites that focus on specific surnames — there’s the Smith Project and the Jones Project and the Fitzpatrick Project. In fact, Colleen knew there were over 200,000 publicly available Y-DNA profiles and she had the software to mine them.

When she compared the canal murderer’s Y-DNA to these publicly available profiles, she got eight matches, all with the same last name.

“She gave us a last name, Miller,” says Roestenberg. “We did a follow-up and found his name in our files. We found a suspect with that name who we had contacted years earlier.” Detectives had talked to Bryan Patrick Miller twenty years earlier, when he was nineteen. At the time, he denied involvement and was dismissed. Now he became their number one suspect.

Of course, they needed to confirm that they had the right man. So the detectives surreptitiously collected Miller’s DNA (since the criminal case is still pending, he won’t say how exactly they did this) and sent the sample to the lab so that the genetic material could be compared to the DNA left at the crime scene.

Days later, as the detectives gathered for a weekly meeting, an analyst from the lab called. Could they come over? Like right now?

“They literally walked over,” says Roestenberg. “That never happens. The lab employees never just walk over to the police department to personally deliver information. And they came in and said, ‘We got him.’”

Roestenberg was so shocked all he could say was, “Are you sure?’” To which the lab technician replied the chances they were wrong was one in several quintillion. “Yeah, it’s definitely him. I do believe I shed a tear.”

It was eight p.m. and Fitzpatrick was at dinner with a friend when the detective called. “He said, ‘You were right, you were right! His name’s Miller!’”

The next day a SWAT team arrested Miller, now forty-three-years-old, for the murders of Angela Brosso and Melanie Bernas. He goes to trial soon and police say he is a suspect in several additional cold case murders, perhaps dozens.

“Without Colleen getting involved, I feel strongly that this case would never have been solved,” says Roestenberg. “I don’t know if you ever get closure, but, yes, it was good for the family.”

Thanks to Colleen, police had been given a new tool to crack cold cases. And there was one dark mystery from the Pacific Northwest that called for Colleen’s particular set of skills.

Case Study: Lori Erica Ruff

The day before Christmas, 2010, the body of Lori Erica Ruff was discovered inside her car. She’d parked in her in-law’s driveway before she shot herself. Near her body were two suicides notes, one addressed to her “wonderful husband,” the other addressed to their young daughter, to be opened on her eighteenth birthday. At the time, Lori was separated from her husband, Blake Ruff, and Blake had moved back into his parent’s place. The suicide notes offered no explanation for the suicide — they were described as the disparate ramblings of a disturbed mind.

Lori met Blake in a bible-study class in 2003. This was in East Texas, where Blake’s extended family were from. When his parents inquired about Lori’s own family, she gave only vague replies — she was from Arizona, she said, and her parents were dead.

After Lori’s funeral, Blake’s brother-in-law, Miles Darby, drove out to Lori’s house in nearby Leonard. He searched the place for some clue, something to explain why she killed herself. The house was a mess. Hidden in a closet they found a lock box. Miles pried it open with a screwdriver. Inside was the birth certificate of a girl named Becky Sue Turner, a two-year-old who had died in a house fire in 1971, in Fife, Washington.

Investigators learned that someone had requested this birth certificate from the records office in Bakersfield, California, in 1988. Later that year, Turner’s birth certificate was used to obtain a state ID in Idaho. Three weeks after that, a woman calling herself Becky Turner appeared before a judge in Dallas and legally changed her name to “Lori Erica Kennedy,” further distancing herself from her true identity, whatever it had been.

Try as they might, the police could not figure out who Lori really was prior to 1988 or why she took her real name to the grave.

Colleen read an article about Lori’s mystery in the Seattle Times and immediately reached out to lead investigator Joe Velling, whose job it was to track down the fraudulent use of social security numbers for the SSA. She explained, as best she could, how her team could find Lori’s real family if they had access to her DNA. But nobody had Lori’s DNA. No problem, said Colleen. They had the next best thing — Lori’s daughter.

Lori had wanted a child more than anything and she had tried repeatedly to have one with Blake but the pregnancies ended in miscarriage. Finally, after fertility treatments, she gave birth to a girl, in 2008. By the time Colleen got involved, Blake had already submited his DNA, and the DNA of his daughter, to 23andMe, a genealogy website. 23andMe has a tool that looks for common markers and removes them. With a couple clicks, Colleen was able to filter out the part of the girl’s genetic code that had come from her father and isolate the part that had come from her mother. A search was then run on the DNA that remained which produced several hits with a man named Michael Cassidy at the top. The website said he was probably the dead woman’s first cousin. Colleen tried to email Cassidy, but he never replied. But soon, another close match was made and Colleen was able to connect this new profile to Michael Cassidy as well. Knowing both of their names, she was able to triangulate the right Michael Cassidy. His family was from Philadelphia.

Velling flew to Philly and dropped in on a member of the family while she was at work. He tried to explain how Colleen had isolated the DNA of a dead woman from her daughter’s spit and then out of frustration just showed her photographs of Lori. “My God, that’s Kimberly!” she said. Kimberly McLean was her cousin-in-law and she had disappeared in 1986. The day she turned eighteen, she left a note on her pillow asking her mother not to look for her.

We may never really know what drove Kimberly McLean to change her name not once, but twice. Every family has its secrets. Every person has their own demons. And sometimes people just want a change. But our parents’ DNA will always a part of us.

A quirky, socially-awkward civilian had become law enforcement’s new secret weapon. Without meaning to, Colleen Fitzpatrick had become a post-modern Sherlock Holmes. And every Holmes needs a Watson.

Case Study: Margaret Press

Before she found genealogy, Margaret Press fell in love with linguistics. This was at Berkeley, in the late sixties — where the culture was evolving day by day. Margaret’s mother was an activist in Pasadena and she’d taken Margaret to political protests as a girl, where she had witnessed the power of words in the signs and chants used to fight racism and McCarthyism. By the time she got to Berkeley, revolution was the word of the day. Not just in the streets but within the study of linguistics as well. A young rockstar of a linguist, Noam Chomsky, was challenging long-held beliefs about the origins of language. Chomsky proposed that the capacity for language was innate in humans — that we are born with an understanding of the structure of language that is not learned, as unlikely a thing as a child who never played chess knowing where each piece goes at the beginning of his first game.

“Suddenly the planets were going around the sun, not the earth,” says Margaret, recalling the excitement she felt reading Chomsky’s theories for the first time. “This universal structure of language has to be hard-wired inside us. And it is. Like our DNA. If you work backward from any language you will see where it diverges from a common, shared language hundreds of years ago.” Margaret explains how in most IndoEuropean languages, the word for “father” begins with either a “p” or an “f.” Like a mutation on the Y-chromosome, you can figure out which languages are related to each other based on which letter they use today.

For her dissertation, Margaret compiled a descriptive grammar of Chemehuevi, a nearly-extinct Native American language. After grad school, she found work writing in the language of computers and worked in software development until she retired two years ago. The software work was always meant to supplement her other passion — writing murder mysteries. Margaret is the author of several fiction and nonfiction books based in Salem, Massachusetts. In 1996, she published Counterpoint, which detailed her research into the real-life murder of Martha Brailsford.

It was another mystery writer, though, who inspired Margaret to test the boundaries of forensic science.

In 2000, the novelist Sue Grafton learned about a cold case from Santa Barbara as she was casting about for a mystery she could use for the next book in her Alphabet series. In 1969, a young woman’s body was found by hunters in a quarry, her murder never solved, her identity never recovered. There were scant clues — she’d buck teeth and new fillings. She wore bell-bottoms and horseshoe earrings. Grafton became enamored of the case and used it for the basic plot of Q is for Quarry.

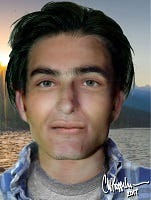

In 2001, Grafton paid to have the woman’s body exhumed. DNA was collected. A facial-reconstruction was done. But none of the leads panned out.

Margaret read about the case and wondered if she might be able to help. She knew that adoptees in the United States were having luck tracking down their parents by having their DNA sequenced by companies such as Ancestry and 23andMe. Why couldn’t that same technology be used to identify the Santa Barbara Jane Doe? So she contacted the Sheriff’s Office. “They wouldn’t return my calls,” she says. “They thought I was a crank, like the psychics who call and say they know who the murderer is. A genealogist calls and says I can solve your case? Okay, right.”

What she needed was credibility. Colleen had street cred. She was already working with law enforcement on similar cases. So Margaret reached out to Colleen on Facebook and laid out her plan — she wanted to get the dead woman’s genetic profile from the detectives in Santa Barbara and upload it into the 23andMe database. It would surely kick up a relative match, a second cousin in Boise or something.

But Colleen and others said such a thing would be impossible. Ancestry and 23andMe do not allow users to upload their own genetic profiles. They test the samples sent in by subscribers themselves and then use proprietary software to find specific markers known as single nucleotide polymorphisms, which you’ll see written as “SNPs”, commonly called “snips.” These markers are then compared to other profiles in their database. They brainstormed ideas — perhaps they could attend a symposium where executives from the genetic companies would be present and convince them that they should allow these uploads.

And then a hobbyist figured out a workaround. It was a member of their Facebook genealogy group — he’d submitted a DNA sample of his dead father (gathered from a tissue sample collected during a hospital stay) and had its entire genome sequenced — not just the Y-DNA that many genealogists relied on to trace lineage, but also the DNA from the other twenty-two chromosome pairs inherited from both parents — what’s called autosomal DNA. And while the private ancestry companies don’t allow uploads, they do allow users to download a text file that contains coded information about specific markers that were identified in their DNA. That text file can then be uploaded to a public repository of autosomal DNA on the web, called GEDmatch. The GEDmatch software then looks for matches between all their user’s data sets. Using a program to isolate these same snips from the whole genome data a file could be created and uploaded. It worked! The man succeeded in created a 23andMe file for his father on his own. GEDmatch located the man’s relatives and Colleen and Margaret found their solution. The same strategy could be used to identify any John or Jane Doe.

“It was the right moment, the perfect storm,” says Margaret. “The public databases were getting bigger, and the genetic testing was getting cheaper. Suddenly, entire-genome testing was affordable.” Margaret still holds out hope that one day the private companies will see the benefit of working with them, too. “We’d have access to another 15 million profiles if Ancestry and 23andMe allowed clients to upload data. We could solve these cases lickety split.”

Grafton died last December. The Santa Barbara Jane Doe has yet to be identified. But Margaret hopes for an answer soon. “I would have loved to tell her we’re going to do this case.”

From that moment on, Colleen and Margaret have spoken nearly every day. Colleen contacts law enforcement and Margaret manages a volunteer army of genealogists that gather to discuss leads in their private Facebook group.

“She’s the nuts and bolts,” says Colleen. “I’m more of the marketing end. I’m more the one with the contacts, who knows the agencies, knows how to speak to them. Our personalities are very compatible.”

Together, Colleen and Margaret founded the DNA Doe Project, a nonprofit organization that uses autosomal DNA to identify John and Jane Does. The project also helps raise funds for agencies that want to use their services but who can’t afford it. What they needed now was proof of concept.

Case Study: Lyle Stevik

This mystery began on September 14, 2001, three days after the towers came down. A young man checked into the Quinault Inn, a motel in Amanda Park, Washington, under the name “Lyle Stevik.” He had no luggage. No I.D. Only the clothes on his back, some cash, and a toothbrush. Three days later, he was found hanging from a belt tied around a clothes rod in the closet of his room. His name was fictitious, a character from a Joyce Carol Oates’ novel, and the address he gave to the clerk led to a hotel in Idaho.

Armchair sleuths wondered if the man was part of the terror cell that had orchestrated the September 11 attacks — did he kill himself before the feds could catch him?

Police collected his DNA, sent it to the lab, and then entered his profile into the F.B.I.’s Combined DNA Index System — known as CODIS — the government’s private database of felon DNA. No match. But that only meant he’d never been to prison.

Colleen read about the case and reached out to the local coroner, Lane Youmans. It was the perfect mystery for the DNA Doe Project to solve. Youmans was game but there was a problem — the county didn’t have the money for testing. So Colleen and Margaret organized their first “DoeFundMe” campaign to raise funds for a new, autosomal DNA test. Redditors and members of their Facebook group opened their wallets. They raised the $1,500 needed for the testing within twelve hours.

Youmans sent Lyle’s DNA to the lab, where it was sequenced and then converted to electronic data and saved on a hard drive. Colleen then had a bioinformatics expert extract specific snips from this data that are also used by GEDMatch. The markers from Lyle’s profile were then compared to the markers from other people’s profiles on the website (the software does this — nobody can ever see or directly access someone else’s DNA profile). Markers found in Lyle’s DNA matched to probable distant cousins in Northern New Mexico and the greater Four-Corners area. But it was hard to narrow it down from there. The problem was endogamy.

Endogamy occurs in isolated community groups — most notably Appalachia, where cousins intermarry and people are sometimes related to each other in five different ways. In the Lyle Stevik case, the results brought Colleen and Margaret to a region of the United States that originally settled by Spanish conquistadors who took Native Americans as wives. Their descendants had been isolated from the greater world and there had been a lot of intermarriage. The team felt they were close but it was going to be difficult to hone in on the man’s identity because of the intertwined branches of his family tree.

GEDmatch has lots of nifty tools. One of them is a program called “Are my parents related?” Colleen clicked on it, expecting to find that Lyle’s parents were related like everyone around them, but they were not. Colleen knew that this must mean one of Lyle’s parents were not from the same region. Another researcher in their group noticed a particular snip on Lyle’s Y-chromosome that matched to a man from south America — which suggested his father likely came from there, too. And that meant his mother must be the parent who was native to the Four Corners area.

The team spent hundreds of hours building out family trees for the matches. One lucky volunteer contacted a family member from this region to help them make better sense of the family tree. That family member mentioned that she had heard that a young man, distantly related to her, had gone missing some years ago. They had stumbled onto their answer sooner than expected.

“These cases are like trying to figure out a giant Sudoku puzzle,” says Margaret. “And this solution fit the puzzle.”

Case closed. Sure. But the state of Washington does not release the names of suicides. And the family of the deceased did not come forward, publicly.

“In many cultures there’s shame associated with suicide,” Margaret explains. “My brother committed suicide. It was never in the papers. The publicity would have added to the pain. I can think of no reason this family would want to make it public.”

That made some Redditors who had donated money very angry. “They’re saying, ‘We have a right to this knowledge. We’re entitled to know who he is,’” says Margaret.

It was an unexpected reaction but Colleen and Margaret were not discouraged. Lyle’s case and the others they were working on proved that the DNA Doe Project worked. “This was unprecedented,” says Colleen. But there was a growing concern that others in the genealogical community would view what they were doing as an invasion of privacy. Each time they solved a new case, it brought more attention. Eventually, GEDMatch would have to decide what was permissible. And what would happen to their efforts to identify their John and Jane Does if the database they relied on suddenly changed its terms of service? What if it simply shut down? “If GEDmatch rolled up the sidewalk, we were toast.”

Margaret sighs. “And then the Golden State Killer happened.”

Case Study: The Baby-Dick Killer

It seems callous to reduce the evil of this man to a paragraph. But there’s simply too much to give every last horror its due.

His crimes began with burglaries (about a hundred), which advanced to rapes (at least fifty), and then to murder (at least thirteen). His killing fields were the suburbs of Sacramento, Modesto, Visalia. The serial killer’s reign lasted from 1974 to 1986, and then he went silent. Some suspected he had died. The police have given him many names over the years — The East Area Rapist, the Original Night Stalker, the Golden State Killer. Redditors preferred another moniker, though. Online, he was known as the Baby-Dick Killer, so named because his victims claimed their attacker had a micro-penis. DNA linked all of these crimes together but the perpetrator remained unknown — police found no match in CODIS.

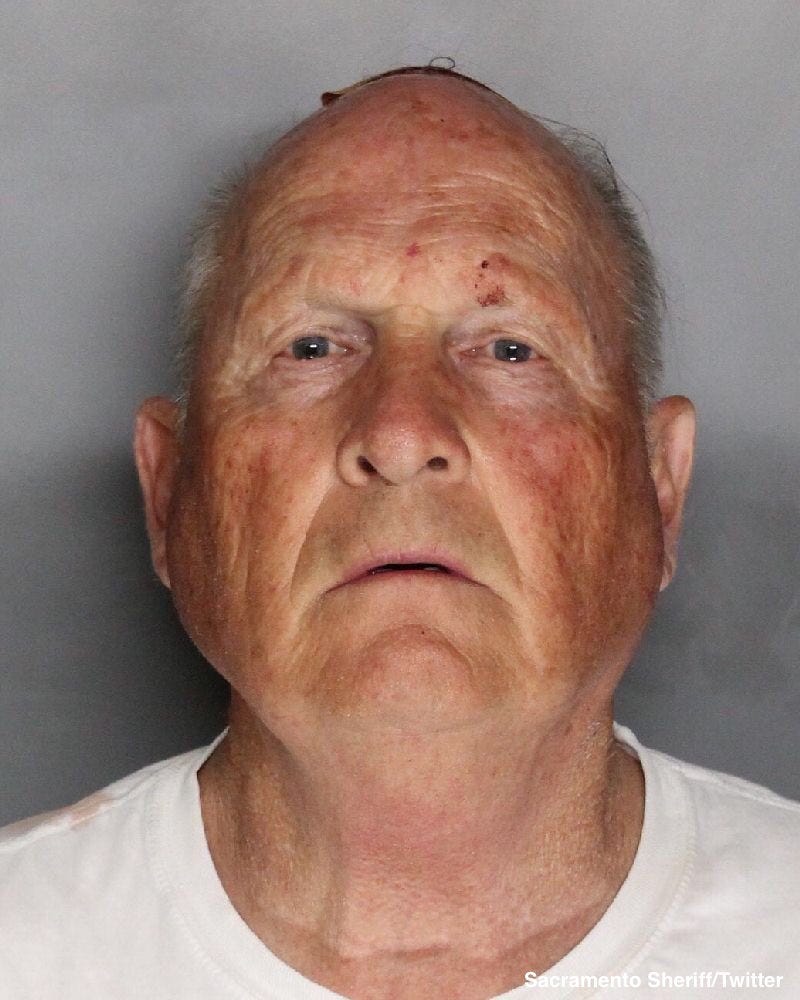

Paul Holes, a retired investigator for the Contra Costa DA’s officer, consulted with his own forensic genealogist, a woman named Barbara Rae-Venter, a retired intellectual property attorney. They compared the Golden State Killer’s DNA with the profiles on GEDmatch, and identified possible relatives. From there they narrowed the list down to a couple possible candidates, which pointed them to Joseph DeAngelo, a former police officer from Citrus Heights.

80-year-old Curtis Rogers was in bed the morning of April 25, reading the news on his computer as is his routine. That’s when he saw the breaking news — the Golden State Killer was caught — and the police had used his website to do it.

“I could feel my hair turn gray,” says Rogers. In another life he worked in international business, servicing clients like Quaker Oats and Mennen. He’s retired, now. But not less busy. GEDmatch was his idea. But he’d never envisioned where it would lead him. “I think I sat there and just tried to absorb the meaning of what was happening. I looked outside. There were antennas. There were reporters at my door.”

Rogers was faced with a dilemma — what was to be done about GEDmatch, what responsibility did he have? “I was very concerned,” he says. “Were we violating the privacy of our users, allowing these forensic genealogists to compare a suspect’s DNA to their profile? At the same time, here was this killer that made Jack the Ripper look like a choir boy. I did a lot of thinking. The ethics are very bothersome.”

Rogers is not a crime fighter by choice. He was a member of the Rogers surname project, and claims to be the third cousin, three times removed, of Winston Churchill. Rogers had become frustrated by having to make so many calls to members of other surname projects in order to trace back his family tree. So out of necessity came a simple idea — what if he were to build a website that could serve as a central clearinghouse for autosomal DNA data?

It began in 2010 and he named it GEDmatch, after GEDCOM (Genealogical Data Communication), a data format used for comparing DNA profiles that was developed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Genealogy is a big part of the Mormon faith because of their belief in baptism-by-proxy. If they can specifically identify a person who died, no matter how long ago it happened, they can be saved if a member of the church is baptized in their place. Their mission is to save us all.

GEDmatch was built so genealogists could analyze their DNA, not to catch criminals. But in the end, the ends justified the means. “The dam was broken with the Golden State Killer,” says Rogers. “There’s no going back. What we need to do is educate our users.”

GEDmatch will remain up and open, he says, and can be used to track serial killers and rapists. It’s a new era for DNA.

“The police were used to things that were easy,” says Rogers. “Black and white. Fingerprints are either a match or not. DNA matched a suspect or it didn’t. Now, DNA is no longer black and white, no longer yes or no. It’s more complicated now. The police have to use people like Colleen. Experts at finding people. Law enforcement can’t do it alone right now because they simply don’t know how but maybe in the future they’ll train their own experts.”

Currently, there is nothing regulating this new field of investigation and genealogists are very concerned that Congress will tackle the issue.

For now anyway, the new frontier of forensic genealogy is wide open. Colleen has begun accepting criminal cases through her private company, Identifinders International. The DNA Doe project remains dedicated to giving names to John and Jane Does.

Case Study: Joseph Newton Chandler, Revisited

In retrospect, it was long, twisted chain of events that brought the Joseph Newton Chandler case to a close. If Colleen had not won that science fair, if a retired businessman had not had an idea to create an open database of DNA profiles, if the case had not landed on U.S. Marshall’s Pete Elliott’s desk… it’s hard to look back and not see some cosmic design to it all.

Elliott heard about Colleen after she solved the Lori Erica Ruff case and asked if she could help him. The lab had already isolated the man’s Y-DNA profile. In that profile were segments of DNA where the nucleotides (the A-G-T-C bases you learned about in grade school) repeated. Everyone’s DNA has these small, repeating bits of genetic code, in different places — what’s called a “short tandem repeat,” or STR. Colleen compared the STR profile generated on the case to hundreds of thousands of Y-DNA profiles stored online at places like YSearch.org. Out of all of those available profiles, only one matched all seventeen markers. That person’s last name was Nicholas.

This line of Nicholases descended from a colonial immigrant, George Nicholas. George’s son was the first treasurer of the colony of Virginia. It was a prominent family with old ties going back centuries. There were literally thousands of descendants.

So Elliott, at Colleen and Margaret’s request, resubmitted the DNA to the lab for full genome sequencing. When the data came back, Colleen uploaded the file to GEDmatch, where the new information was compared to the other autosomal DNA files in its database. This identified hundreds of distant relatives.

“We were working with fumes here,” says Colleen. So they requested that the lab test the DNA extract one more time — a risky gamble, since this would destroy the remaining DNA the lab had for this man. Once it was gone, there could be no more tests. The lab came back with a slightly different data set this time. That’s when Margaret suggested they combined two files. “I explain it like having two photographs where the resolution is not great and then overlaying them to fill in the face in the picture,” says Margaret. This time GEDmatch identified several relatives they’d never seen before. And one new match led them to a woman named Schreiber who had four sons with a man whose last name was Nichols.

Three of the boys had a date of death. The fourth — Robert Ivan Nichols — did not. The DNA Doe volunteers scoured social media for more information about this family. They searched public records and phone numbers. And one very smart sleuth noticed an odd coincidence — she’d found that the Nichols family home was 1823 Center Street in New Albany, Indiana — when Chandler had filled out his rental agreement, he’d listed 1823 Center Street, Columbus as an address.

“It wasn’t a coincidence,” says Elliott. “Liars always lie close to home.”

Soon, Elliott stood on the doorstep of man named Phil Nichols, who he now believed was the mystery man’s son. “I drove down with another Marshal and knocked on his door. When he opened the door, it was like Joseph Newton Chandler was standing there. They looked so much alike. I knew we had our guy.”

Of course, that was only half the mystery. Elliott knows the man’s real name, now, but he still doesn’t know what Nichols was running from. What he’s been able to gather from family stories and scarce public records is that Nichols served on the USS Aaron Ward, which was bombed by the Japanese during World War II. He suffered wounds in battle and burned his uniform when he returned home. In 1965, before he became Joseph Newton Chandler, Nichols lived in Napa County, California — a time and location familiar to those who have hunted the Zodiac Killer. Authorities are searching for a connection but Colleen believes the answer will be mundane and personal, like Lori Erica Ruff.

“I think it’s more likely we’re dealing with a man who suffered from PTSD from the war, which caused paranoia,” she says.

Final Case Study: The Somerton Man

Mountain climbers have their Everest. Arm chair sleuths have the Somerton Man.

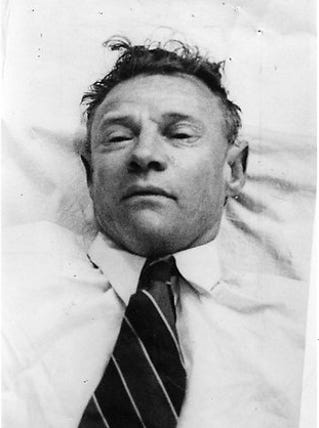

It begins with a body found on Somerton beach, just south of Adelaide, Australia, in 1948. There was no discernable cause of death and to this day investigators are unsure if the man was murdered or if he committed suicide, or if he died of natural causes. He had no I.D. The tags had been cut off his clothes. There was comb in his pocket from America and some Juicy Fruit gum. Oh, and hidden in a fob pocket was a piece of paper torn out of a book, a single line of text, “Tamam Shud” — Persian for “It is ended.” The very book from which the page was ripped — a collection of poetry called The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam — was eventually located. Someone had tossed it into the back seat of a parked car and the owner of the vehicle came forward after hearing the details of the case in the news. Inside the book were two additional clues — a message written in code and the phone number of a local nurse. The nurse claimed to know nothing. She said she didn’t recognize the dead man on the beach. To this day, his identity remains unknown.

And here we have another simple twist of fate — a biomedical engineering professor from Adelaide named Derek Abbott, found himself sitting in a laundromat, in 1995. Bored, he flipped through a stack of old magazines. One had a write-up on Australia’s most notorious unsolved mysteries. He was transfixed by the tale of the Somerton Man. He never forgot it and when a newspaper published the secret code, in 2007, he thought it would be a fun puzzle to share with his students. They used statistical analysis in an attempt to identify the cypher. But the solution proved elusive.

“When you have a good math problem, it fights back at you,” he says. “If we’ve got ourselves a good problem, it isn’t a slam dunk. You need tenacity to see the problem through. This is no different.”

Abbott came to believe the strange message was not a substitution code at all. Perhaps each letter represents an entire word, combining to make a sentence that had special meaning to two people or maybe it represents a passage or poem from another book. But the cypher wasn’t the only way to identify the Somerton Man. What he really needed was DNA.

Abbott pushed the authorities to have the body exhumed, to no avail. Luckily, the local police museum had kept a plaster cast of the man’s upper body and some of his hairs had stuck to the plaster. Abbott obtained a hair sample from the museum and sent it to a lab, which was able to recover the full mitochondrial DNA profile of the mystery man. It was just enough to identify him as being of European descent, which they already knew from pictures of his body.

Abbott had another thought — what if the Somerton Man really did know that nurse, the one whose number appeared in the book with the secret code? Through his contacts with the police, Abbott discovered her real name, which had never been published — Jo Thomson. He tracked her down only to discover she’d died a couple years before. However, she left behind a son, born around the time the Somerton Man was found, a child who had a peculiar dental deformity — he had no lateral incisors — which made it look like his pointy teeth were closer to the front, giving him a vampire-like smile. The Somerton Man had this same, rare deformity. There was a good chance Thomson’s child was the dead man’s illegitimate son.

When Abbott sought out the son, he learned the man had died just a few months prior and his body cremated.

“But we do have somebody else,” he says with a smile. “We have my wife’s DNA.”

See, when Abbott went searching for Thomson’s son, he’d met the man’s daughter. They fell in love. They got married. They now have three kids of their own — children who may be the great-grandchildren of the man Abbott has been trying to identity for over twenty years.

Abbott met Colleen when she came to Adelaide on a book tour. They’ve been working the case together ever since. Early results have led them to Virginia, where Abbott believes the Somerton Man’s relatives may live to this day.

However, Colleen cautions not to be too excited for the answer. She doesn’t believe he was a spy or anything so cool. “I think he’s going to be just some guy who died on the beach.”

Now that police know what a forensic genealogist can do, Colleen’s phone rings incessantly. She still does most of her work sitting at a small table in the kitchen of the same townhouse she’s lived in for decades. “I’m getting calls and emails every day. I’m working on a dozen cases.”

Her house is not large, a couple rooms and bedrooms upstairs. She sublets one of her rooms to a friend. For her dream job to survive, the DNA Doe Project will need funding.

Her siblings are not so worried, though. They remember the girl from Lakeview who found a way to get all the beads she ever needed. “She loves a challenge,” says her sister, Bebe. “Maybe it’s in her DNA.”

Colleen’s brother, Tim, is a part-time deputy back home, runs search and rescue boats when he’s not designing Christmas decorations for fancy businesses in four states. “I’m really proud of her,” he says. “It puts a smile on her face which she hasn’t had in a long time. I’m enjoying watching her. It’s tremendous.”

No matter what happens, Colleen and Margaret have each other’s back. “When you work these cases, you feel that insipient gloom and it can affect you,” says Margaret. “We rely on each other and our team and we focus on the excitement of being the ones to solve a case. And we are. We’re solving them doe by doe by doe. It’s a jungle of bad out there but we’re chopping through it.”

There’s a picture of the Dalai Lama hanging on Colleen’s wall. It’s signed. “I don’t know what the reason is I find myself here, now,” she muses, thinking on the events that stretch back to New Orleans and a simpler time. “Was it to bring closure to these cases? It could be. I might have fulfilled my purpose ten years ago. How do I know? You just gotta do what you can.”